On his visit to China with his father and uncle, the legendary Venetian explorer and merchant, Marco Polo met Kublai Khan, the fifth khagan emperor of the Mongol Empire and the founder of the Yuan Dynasty. Kublai Khan was impressed by Polo’s brilliance and modesty and chose him as his foreign envoy and sent him on a number of diplomatic missions as his representative around the empire and Southeast Asia, including in modern-day Burma, India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

Route of Marco Polo

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

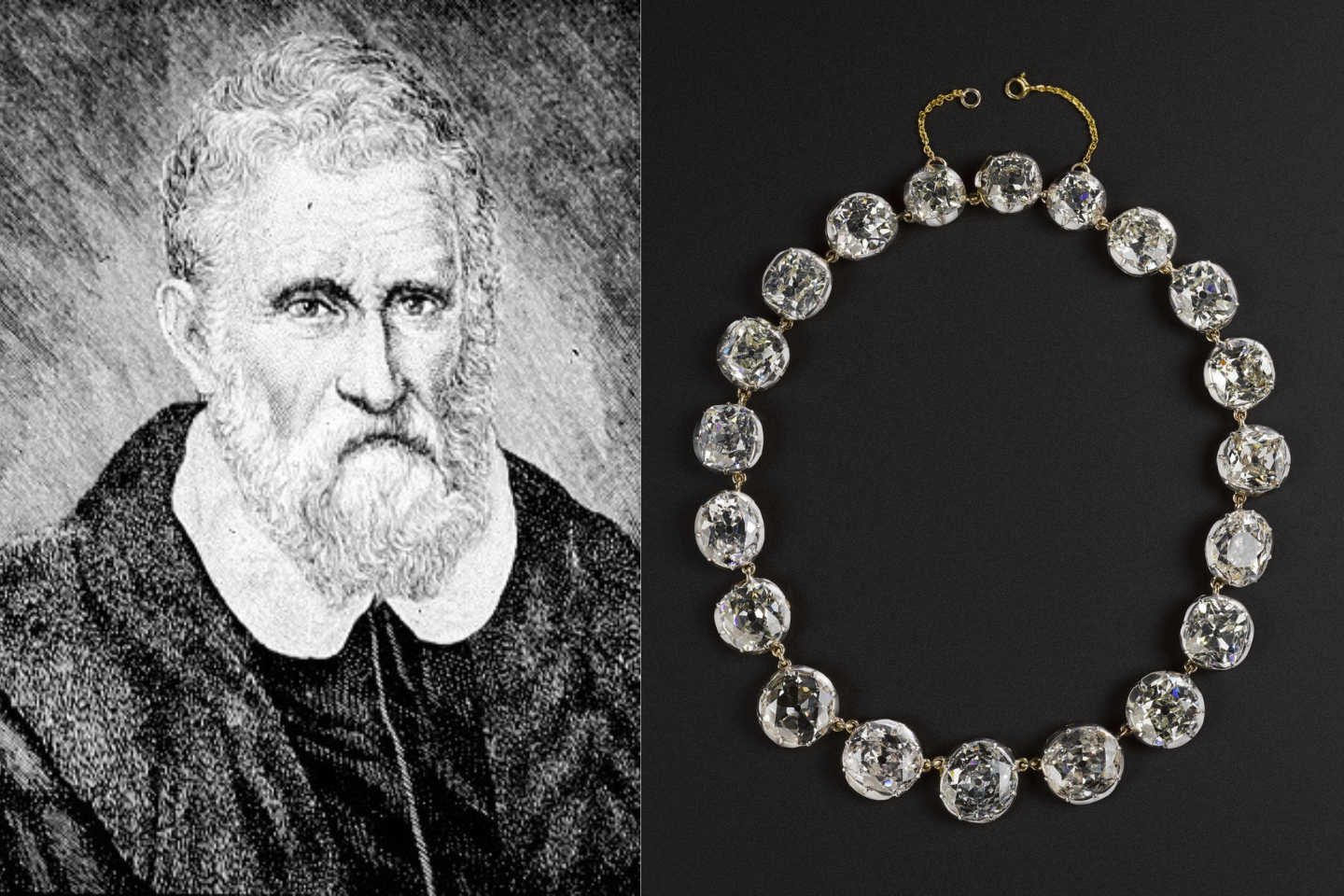

On his way back from China to Venice in 1292, Polo journeyed through India. He made a pit break at a location which afterward came to be known as Golconda, and it was there that he learned about the now-famous Golconda diamonds. Polo provided a pretty credible depiction of these jewels, sprinkled with parts of fantastical storytelling, to inform the west about their origins despite not having personally visited the diamond mines.

Polo’s ‘Scintillating’ Tale of Facts and Fantasy

When documenting his travels through India and his findings of Golconda, Marco Polo peppered his factual accounts with bits of fantasy. For example, when he tells us in his accounts that the place had towering mountains and experienced heavy rainfall in winter. And once the rain got over, one could find a lot of alluvial diamonds by the riverbeds.

Or when he states that the kingdom of Golconda was the only kingdom that produced diamonds in abundance and that they were large in size. And that the region's kings and princes were given exclusive access to the largest, best-quality diamonds, pearls, and other precious stones. This is demonstrated by the fact that during the time, the Golconda mines were leased for a year with the understanding that the king would own all diamonds unearthed weighing ten carats or more, while all other diamonds would belong to the leaseholder.

Golconda in 1733 AD

Image courtesy: Wikipedia

However, when he speaks of the enormous deadly serpents that lived in the mountains, the deep and unreachable valleys between the mountains, or the presence of white eagles that stalked the mountains and fed on the serpents, Polo is actually referencing the elaborate Hindu mythology.

The mythology describes the Nagas, or serpents, as the keepers of earthly treasures, including gemstones such as diamonds, which they store in their underworld homes, which are analogous to Polo's inaccessible valleys. The eagles that Polo talks about allude to Garuda, the mythological foe of the Nagas whom it attacks and consumes. Garuda is frequently shown with a serpent in its beak.

A sculpture at the Hoysaleshwara Temple depicting Garuda fighting a naga

Image courtesy: Karnataka Travelogue

Other Accounts of the Brilliance of Golconda

Another account of the diamond mines of Golconda has been recorded by William Methwold, an English merchant and a representative of the East India Company. According to Methwold's records, a sizable force of roughly 30,000 men, women, and children, primarily tribe Gons and Kols, were engaged in various activities. Large open pits were dug into the diamond-bearing layers in these alluvial mines.

Diamond mine in the Golconda region 1725 CE from the collection of Pieter van der Aa—a Dutch publisher known for preparing maps and atlases.

Source and image courtesy: Wikipedia

From the bottom of the hole to the surface, a line of people passed accumulated water and dug-up earth in buckets and baskets. A leveled, sloping area was filled with earth, and it was encircled by a low mud wall with drainage openings. The earth was laid out to a thickness of roughly 13 cm after being wet down to dry in the sun. With a hand-held stone, the resulting clumps were broken, the pebbles were taken out, and the remaining material was sifted for diamonds.

Apart from the account of Marco Polo and that of William Methwold, there are numerous medieval accounts from Europe and the Middle East of the Golconda diamonds, including those of Muhammed al-Idrisi, a Muslim Arab geographer, and Gaius Plinius Secundus “Pliny the Elder”, a Roman author, philosopher, and commander, which emphasize India's significance as a source of fine diamonds.

The Arthashastra, the Ratna Pariksha, and the Puranas are three examples of early Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain scriptures that also talk about places in India that produced diamonds.

From Rise to Downfall: Diamonds That Caused It All

The diamond mines of the world-famous diamonds, which came to be known as the Golconda diamonds were the richest resource of the Golconda Sultanate, with the Golconda market being the principal source of the biggest and brightest diamonds in the world. Ironically though, it also became the reason for its downfall, when the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan succeeded in annexing the sultanate and bringing it under the Mughal rule in 1635 and later appointed his son, Aurangzeb the viceroy of the Deccan region in 1936.

Painting, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, Shah Jahan seated under a canopy, holding one of his four sons. The child may be Aurangzeb, born in the autumn of 1618.

Source and image courtesy: Victoria and Albert Museum

This profile portrait of Prince Aurangzeb (later Emperor `Alamgir “World Seizer” r. 1658–1707) was likely created during one of his terms as viceroy of the Deccan. At this time, the future emperor had established a base at the site that he named for himself—Aurangabad (formerly Khirki). This painting would have been produced by a Mughal-trained artist in the Prince’s palace workshop. This work is an important stylistic bridge between the worlds of the Mughals in the north, and the Deccani Sultans in the central plateau of India. The work is Mughal in its portrait style, and yet has been produced on cloth, a medium more typical of the Deccan, where it was produced.

Source: The Met Museum

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Golconda, once a thriving kingdom built atop a prominent hill and protected by a wall of big granite blocks with numerous gateways, now remains a quaint ruin of palaces, mosques, and other buildings that allude to its previous splendor.