Ornate designs made with precious gemstones encrusted in 24K gold—said to have been born in the royal region of Rajasthan and flourished during the era of the Mughals, Kundan jewelry is perhaps one of the most, if not the most-loved jewelry styles in India, especially that of brides.

According to Bernadette Van Gelder's book Traditional Indian Jewelry—Beautiful People, the Kundan jewelry-making technique is perhaps the oldest technique for setting stones in jewelry using gold in the Indian tradition. According to the book, this technique was first mentioned in the Ain-i-Akbari, the third and final book of Akbarnama, the official account of Akbar's reign.

The incomplete nature of this turban ornament, which is missing the standard jeweled front, reveals the technique of manufacture of most of the enameled and jeweled gold ornaments made under Mughal stylistic influence. They are not solid gold but hollow and filled with lac, a natural resin. The enameling would be completed before the lac was added, and the stones would then be set into the piece using Kundan – highly refined gold that can be pressed into place by the jeweler’s tools without using heat.

Source and image courtesy: Victoria and Albert Museum

The Intricate Art of Kundan Jewelry Making—A Closer Look

Kundan is unmixed gold that is beaten in lengths to form a flat strip. The strips are rolled up around a small flat iron bar (10 cm long and 2.5 cm wide) and worked until each wire overlaps and joins the other after some preparation (heating, cooling, washing, and drying). The end result is pure gold foil, free of any alloying metal.

Rolling mill to achieve a length of thin ribbon

Source and Image courtesy: Traditional Indian Jewellery—Beautiful People by Bernadette Van Gelder

After folding multiple times, the Kundan ribbon (ranging in thickness from 4mm to 7mm) is ready to be divided into small pieces and used. It must be handled with extreme caution and must not be touched by hand to prevent impurities from mixing with the metal. According to goldsmiths, the ability to create high-quality Kundan is the first and most important virtue of their trade.

Kundan ribbons ready for use

Source and Image courtesy: Traditional Indian Jewellery—Beautiful People by Bernadette Van Gelder

The sophisticated Kundan technique enables gemstones of any size or shape to be set into intricate designs. Sometimes, before the entire stone-setting process begins, gold-smiths might fill the hollow frame, known as ghat, with different objects of varying shapes grouped together to form the object. Another option is to let the shape of the gemstone define the ghat's shame.

Since earlier times, certain shapes have influenced the jewelry-making tradition. Squares, triangles, and circles are the most common shapes.

Different shapes put together

Source and Image courtesy: Traditional Indian Jewellery—Beautiful People by Bernadette Van Gelder

The ghat is first filled with wax before setting the stone to strengthen the high-karat gold frame. The wax, along with lead, helps support the gold in larger artifacts. The color may lose luster and turn dark over time.

Different forms of ghat, some already filled with wax

Source and Image courtesy: Traditional Indian Jewellery—Beautiful People by Bernadette Van Gelder

Extra space is allowed for inserting Kundan foil, which is bent over the rim of the gold ghat and serves as a support for the small gold ribbons that hold the gemstone securely in place. Because pure gold is malleable in a cold state, no welding is required. Extra layers of Kundan are applied around the stone, raising the rim slightly above the stone. The Kundan rim can be left plain or adorned with decorative patterns.

Because the stone is mounted in a closed setting, light only enters the stone from the top in Kundan-set jewelry. To maximize brilliance, the stone is tightly wrapped in a shiny metal foil known as daank, which must be made separately for each stone. Originally, the daank was also made of gold, but nowadays silver foil is used with colorless stones such as diamonds, white sapphires, rock crystals, and so on.

Diamond being prepared with silver foil before setting

Source and Image courtesy: Traditional Indian Jewellery—Beautiful People by Bernadette Van Gelder

Joban (red—laal joban, green—hari joban, blue—neel joban) is a colored metallic foil used for colored stones such as ruby, emerald, and sapphire. Like the wax, the foil beneath the stone can also fade or lose color. Scholars use the color shift to determine the time period during which the jewelry piece could have been created.

Diamonds being set

Source and Image courtesy: Traditional Indian Jewellery—Beautiful People by Bernadette Van Gelder

Gold Kundan strip being tooled around the diamond

Source and Image courtesy: Traditional Indian Jewellery—Beautiful People by Bernadette Van Gelder

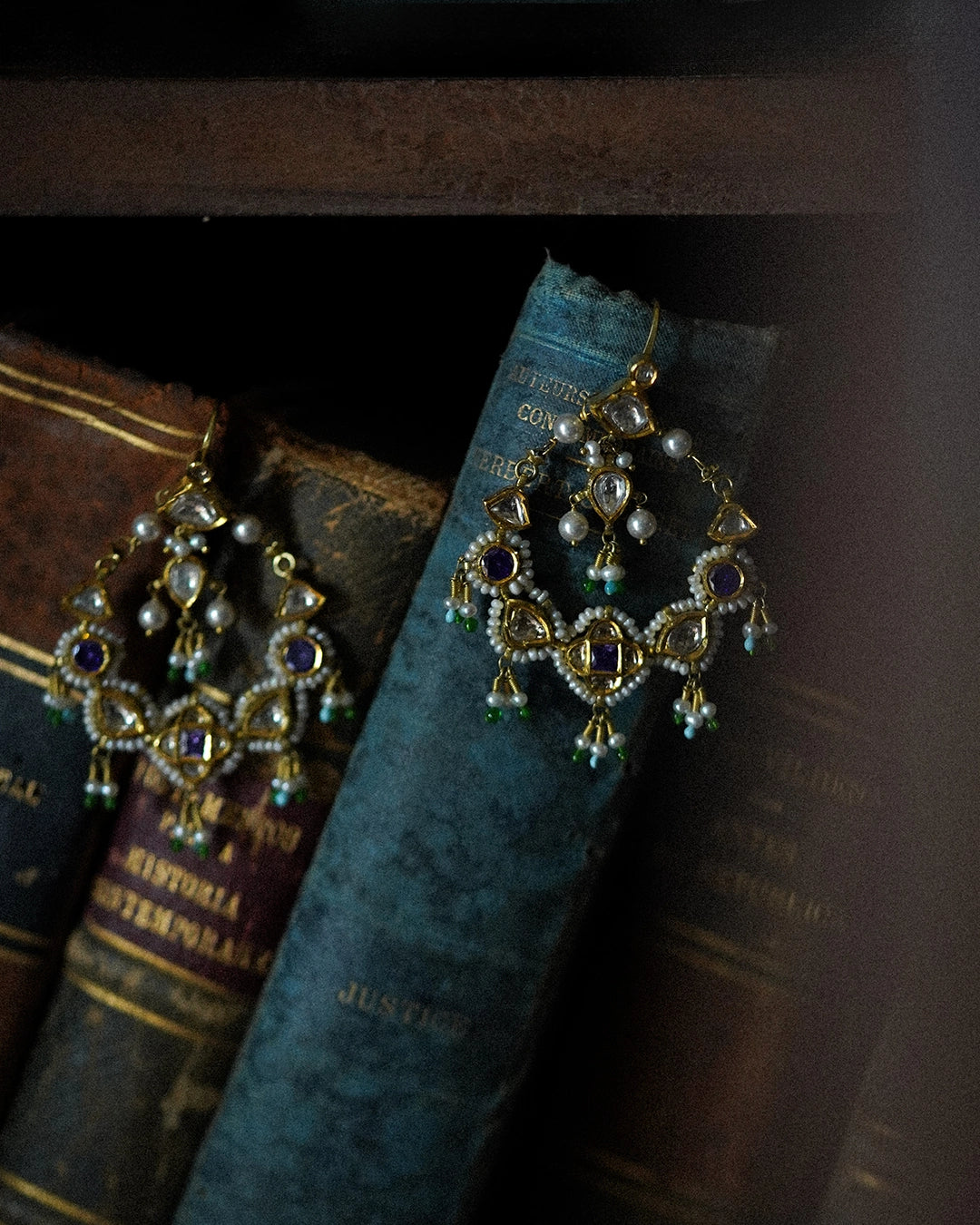

Finished Kundan-technique earrings with embellished pearls

Source and Image courtesy: Traditional Indian Jewellery—Beautiful People by Bernadette Van Gelder

Kundan jewelry has been a tradition for over centuries now and is still practiced today. It is clearly a testament to all the goldsmiths who have kept this traditional stone-setting technique alive on the Indian subcontinent.

Featured image:

Brilliantly colored gemstones and addorsed tiger claws nestle together to form the strikingly shaped pendants of a nineteenth-century Indian necklace. The use of tiger claws as symbols of power and protection is an ancient motif in India, seen also in gold pendants from ninth-century Java and other regions of Asia. The technique of this necklace is that of Kundan, whereby stones are held in place by pure, pressed gold.

Source and image courtesy: The Met Museum